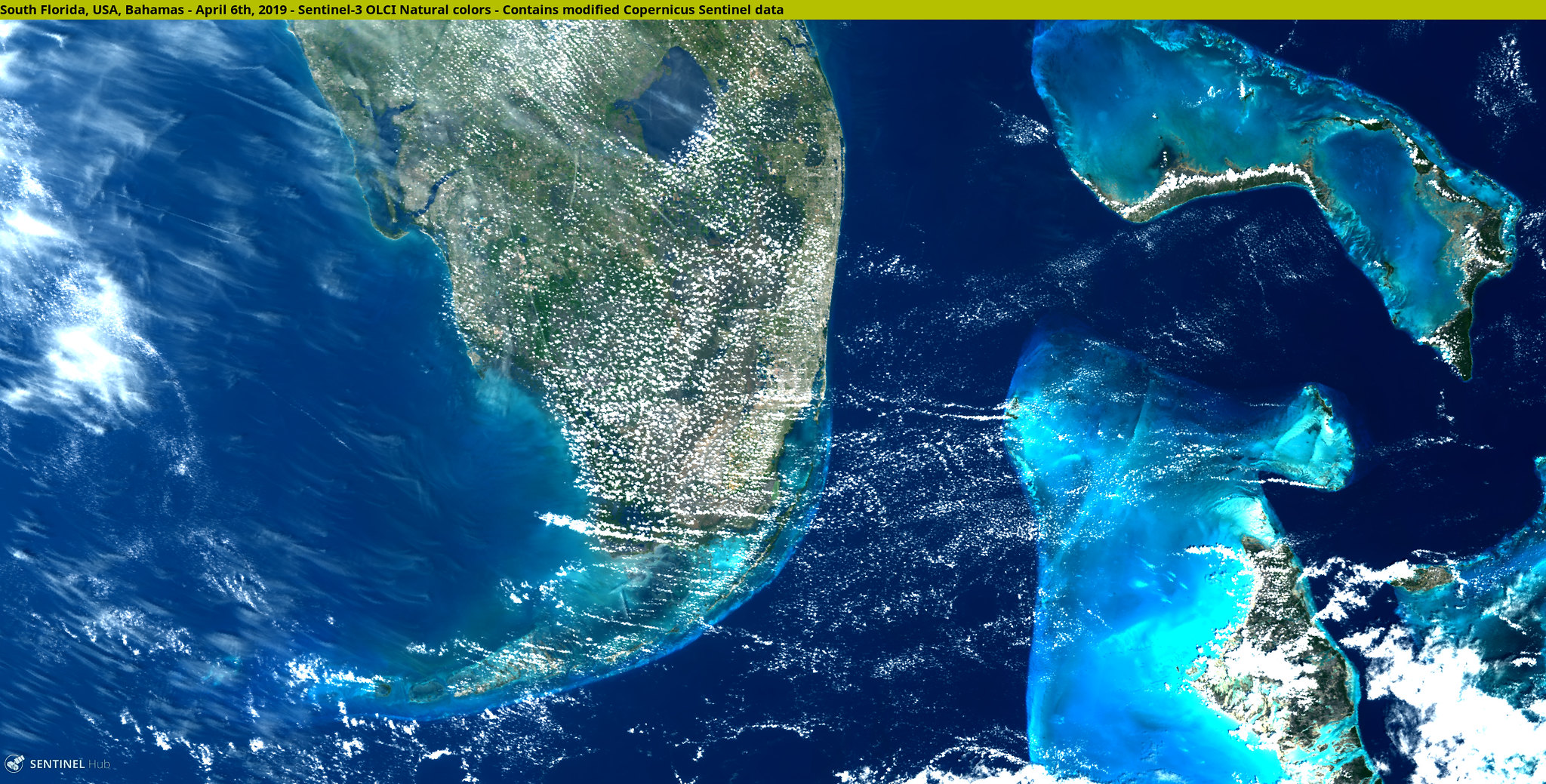

Can we trust satellite data?

When a politician says that satellite data lies and scientists claim it's 95% accurate*, we are more likely to trust the latter. After all, the satellites are reliable.

Aren’t they?

Methods

When we see a satellite image, it may look like a photo, like someone flew above the planet with a camera and recorded everything happening below. The truth is, it's rarely a camera.

There are two methods for observing Earth from Space:

Passive and Active methods.

With passive methods, we register radiation that reaches a satellite. With active methods, we send a radio signal and register what comes back. Both methods have their pros, cons, and areas of application.

Models

In both methods, we register a signal with a specific wavelength. Then, different models help us transform the signal into something tangible. For example, wind speed or ocean color.

These models are based on math and physics.

And often they're empirical –

"Hey, we've got the right numbers for the formula!"**

As you can see, lots of things can go wrong.

– a signal can be distorted in the atmosphere

– a receiver can be interfered by noise

– models can be wrong or biased

Then, how can we claim that the data is trustworthy?

Validation

There is a process to make it work. Every satellite undergoes a long and complex calibration and validation (sometimes referred as CalVal).

This process can be broken down into these two steps:

1. Measure it from Space

2. Measure it on Earth; the same place, the same time

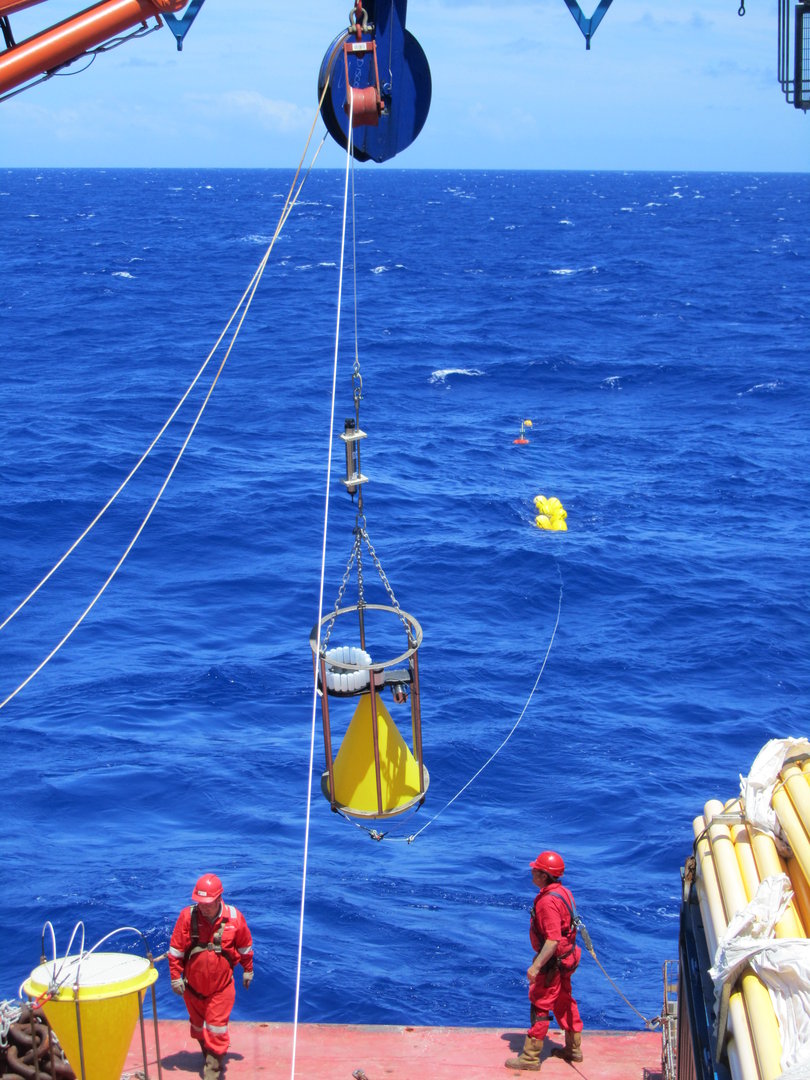

The latter is called in situ measurements.

Taking fiducial reference measurements in the Atlantic Ocean. These are fully traceable, independent measurements collected in situ according to strict protocols. They are used to ensure confidence in data from the Copernicus Sentinels.

© PML

It may sound simple in theory but these experiments require a lot of preparation. They are complex and expensive.

Flags 🚩

Hopefully, satellite knows the nature of every bit of data and it often raises some flags. These flags provide information on a pixel by pixel basis about a large variety of things.

For example, if the pixel represents land, sea, coastline or cloud. In addition to these classification flags, other flags indicate when there are problems with the data, like if it is partly cloudy or if there is glint.

Conclusion

Let's recap.

– a satellite's sensor uses one of two methods to get a signal from the surface

– models help us translate the signal into a physical parameter

– sensors and models are not perfect

– we use in situ measurements for cross-checking

Just like with any other tool, it must be in order. We make sure that measurements are taken carefully and interpreted properly.

Only after that do we get a degree of confidence. May it even be 95%.